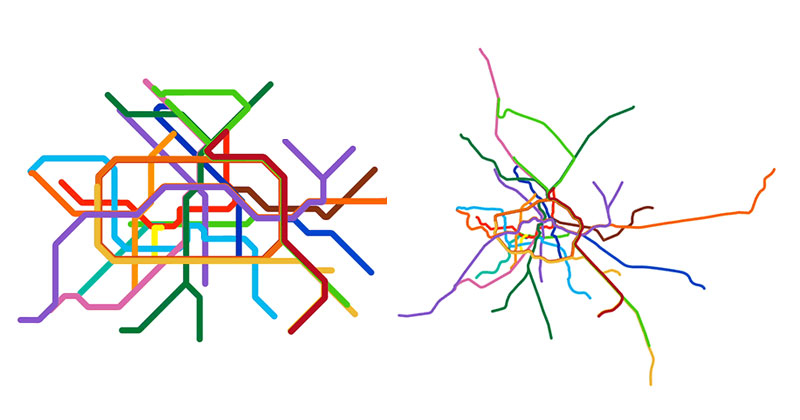

Berlin subway map vs. actual geography, via Reddit

Berlin subway map vs. actual geography, via Reddit

When you start learning about and programming computers, you usually encounter the concept of an “abstraction” pretty soon — there’s a whole Wikipedia article about the term as used in computer science. Abstractions allow you to focus on what different things have in common, so you can elegantly deal with the commonalities in one place without having to handle all the ways in which they are not the same.

If you’re writing the software for a library, you want to define the process for loaning things once, and not separately for books, DVDs, board games, etc. The ability to abstract is, in part, what makes software such an incredibly powerful tool to deal with real-world problems at large scales.

If you rely on abstractions enough, you will also soon learn the hard way that they aren’t perfect. Joel Spolsky speaks of “leaky abstractions” — they “leak out” some of the very details they are supposed to hide from you. Dropbox or OneDrive show you a bunch of files on a shared cloud space like they were on your own computer — until you try to open one that isn’t downloaded yet while your internet connection isn’t working properly.

Another area where “abstraction” is common is mathematics. Henri Poincaré called mathematics “the art of giving the same name to different things”. The first time I read this, I thought it was a joke about how confusing mathematical jargon can get. Turns out it’s actually a statement about abstraction! Abstraction in mathematics, much like in computer science, allows us to see how seemingly different things are, in some important ways, the same. This is very satisfying for someone curios looking for connections and patterns. But more than that, it is extremely useful.

If you discover some fact or method that depends only on these common characteristics of a wide and seemingly disparate array of things, you can suddenly apply it to all of them at once — regardless of the context in which you first came up with it. Information theory was established in the context of telecommunications, driven by questions such as how much information could be transmitted over a less-than-perfect telegraph line. Now, it has found applications across a much wider range of scientific fields and practical problems.

I had mainly encountered the concept of an abstraction when reading about those two fields — computer science and mathematics. But then I realized that people came up with some of the abstractions most impactful in our everyday lives without ever referring to either! The more you notice all the abstractions you interact with, the more coming up with useful abstractions starts to look something humans are just generally interested in — and pretty good at.

Here’s a few examples.

Electricity. It used to be that factories dealt with kinetic energy directly. You’d have a big water wheel in the river outside, and then have an intricate (and probably costly to maintain) system of rods, levers, belts, cogs, and so on that transmitted it across the factory floor to wherever it was needed. Nowadays we have electricity, which is relatively easy to transmit over flexible wires and can be turned into pretty much whatever kind of work you need wherever you need it.

Money. The kind of money we have today functions as an abstract unit that lets you store, exchange, and measure “value” in the same terms regardless of whether you’re interested in t-shirts, your next meal, or a few hours of your time.

Shipping Containers. Imagine going on holiday without a suitcase, picking up each individual item you want to bring, carrying them onto the plane one by one, … — That’s kind of how shipping used to work before containers were invented! Now you just have a box of a standard size and know its weight. Most parts of the supply chain don’t need to care at all about what’s inside.

Commodities. Many of the raw materials and some intermediate products important to human societies today are traded in such a way that most of the actors involved don’t need to care about what share of the stuff they buy comes from this or that farm or mine. This makes global trading a lot easier.

Teams. Teams are also a kind of abstraction — ideally the people on a team complement each other, and different team members pick up the slack at any given time. If you give a project to a team, you ideally shouldn’t have to care about wether one of the members is away for two days the week after next, or whether another member will have a bad day next Tuesday. I first encountered this perspective in Will Larson’s writing on engineering management.

Maps. It’s a cliché by now, but: The map is not the territory! Maps are by definition simplifications of what they depict, a scale of 1:1 wouldn’t be of much use. Some maps trying to serve limited use cases like navigating a subways system are even more abstract.